Reflections on Theory and Practice

In Pursuit of Understanding and Practices That Drive the Greatest Impact in Education

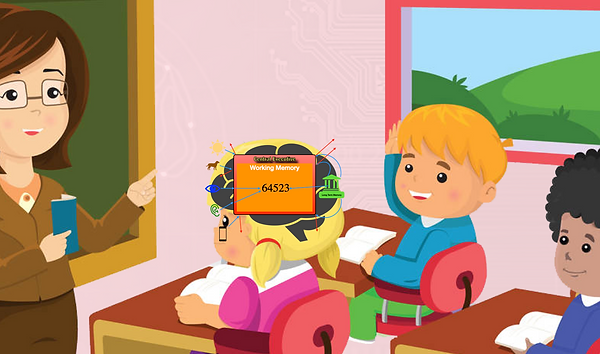

Working Memory

What is Working Memory?

For simplicity we will talk about short term and working memory as the same thing.

Working memory is more of a process than a thing or place in the brain. It takes in new information, holds it, and try's to connect it to schema, or current knowledge webs already established in the brain.

It is the process of holding information while trying to do something with it. Don't think of working memory as storage but a place to temporarily work with information as you try to make connections or do something with it.

There are several aspects of working memory we can break down to help us think about how it is processing information.

-

Central Executive: This controls what information gets into working memory.

-

Phonological Loop: This process deals with the temporary storage of audio input coming into working memory. This includes the voice inside our head when we read or think to ourselves.

-

Visiospatial Sketchpad: This is the process that deals with visual information coming into working memory. This can be coming from outside stimulus or from our long-term memory.

The phonological loop and visiospatial sketchpad help us think about how both visual and audio information are processed at the same time but separately. This understanding can have a big impact on how we teach, especially when thinking about cognitive load.

When the brain receives information from the senses, eyes (seeing), nose (smell), touch, ears (sound), tongue (taste), etc.. it is already being filtered before we even know it is there. This filter is called the Central Executive. It decides what information is important and what information is not important. It is already connecting information from your long term memory on a subconscious level. It will filter out MOST of the information it receives and decide what is important to focus on. This is one reason why a student's background knowledge and experiences play an important role in what they focus on, and why many students will be in the same lesson but get completely different information from that lesson.

Working Memory is extremely limited. To really understand we can look at a popular example.

Directions: Hover your mouse over the example box 1 first for about 3-4 seconds. Only enough time to read the number, then move the cursor off the box. Try to repeat the number that was in the box. Next follow the same instructions for example 2

62345

Example 1

Hover the mouse over this box for 3 - 4 seconds

013146473450

Example 2

Hover the mouse over this box for 3 - 4 seconds

Determining what a chunk is, is a bit more complicated but that simple exercise shows that just a couple more numbers added to a list is enough to overload our working memory.

But our working memory is not just a place where we hold information, like I said it is a place where we work on information. So let's go back to the easy 5 digit example.

Directions: Hover the mouse over the example again, just to refresh your memory. After 2-3 seconds take the cursor off.

62345

Example 1

Hover the mouse over this box for 3 - 4 seconds

Do you remember the number. Now add 1 to each of the digits in the number without going back to the example.

Hover your mouse for the answer

This was much harder. Why? Well this is working memory. Your brain not only needed to hold that "new" information, it needed to do something with it. This quickly fills up the space. It was pulling information from your long term memory connecting to schema you already had, about adding and number sense. It was connecting and changing the new information and old information at the same time.

But an important thing to remember, this is all happening while the real world is still going on around us. If the CE determines something else is more important, it will focus on that thing. This means your student won't successfully connect the information to anything in long term memory and therefore won't learn.

The main take away is, "working memory” is a small and fragile place and getting the right information in there, keeping it there, and doing something with it, is not always simple, and not always as controllable as we or our students would like. Knowing this helps us to be more deliberate and thoughtful when teaching or learning.

Theory to Practice:

A teaching connection

We are constantly overloading student's working memory. That just the truth.

Once we accept this, we can start to teach better. It is inevitable and something that is just going to happen, but the more we can do to limit this, the more we will reach our students.

Unfortunately, what this really implies is that depth or breath. What we all know in teaching but to be true but generally is out of our control. Slowing down the curriculum and teaching for mastery.